jamurfjr

Well-known member

Tenodera sinensis (Chinese Mantis)

Introduction

When asked to envision the stereotypical praying mantis, many Americans conjure up the image of Tenodera sinensis. Along with cousin, T. augustipennis, it's known also as the Chinese mantis. Impressive size coupled with commonness—at least in the eastern half of the US—have influenced this standing. Yet for a child, common doesn't necessarily equate to run of the mill, and such insects are prized for their otherworldly appearance, fascinating behavior, and endearing mannerisms. As the common name implies, the Chinese mantis will always be alien to some extent, for it originated in the far east. Nevertheless, after a hundred years post introduction, it remains touted as an effective means of pest control and now more importantly, an alternative to chemicals(insecticides). Popular amongst gardeners, the oothecae abound just about everywhere—inexpensively sold in local shops and on the internet. All considered, one is subsequently left with little question as to how and why the Chinese mantis has been capturing American affections since the late 1800's.

T. sinensis comes in green, brown, or a combination thereof and blends in very well with its surroundings. Even in brown form, the color green runs the length of the fore-wings' outer edge. A series of vertical stripes/ridges compliment the face. On the ventral thorax, a yellow spot can be discerned between the front legs, and a threat display will reveal a dark set of hind wings. The females measure about four inches. Of considerably less mass, the males are also about a half an inch shorter.

Success in the wild does not guarantee the hobbyist with success in captivity. While later instars and adults may be comparatively easy, raising the smaller nymphs can be downright tough—with many nymphs dying from mismolt or no ostensible reason at all.

Difficulty level: Intermediate.

Development

As with all mantids, insects, etc., temperature and feeding greatly influence development. Under the conditions herein, T. sinensis reaches adulthood in approximately four months, and early instars are achieved in just under two weeks. Later instars take a bit longer. An individual molts roughly seven times. Females may have an extra molt. Lapses in observation and note-taking are responsible for the aforementioned uncertainty. T. sinensis usually lives for eight months to a year. Upon reaching adulthood, females can live another six months. Males, however, live only two to three months as adults.

Behavior/temperament

Individual temperament proves highly variable. Meek exist and so do the audacious. A behavioral spectrum resides between these two extremes.

Cannibalism constitutes a real concern and precludes communal housing beyond early instars.

Camouflage is the first line of defense, but when a Chinese mantis—like many other mantids—is detected and confrontation unavoidable, a different strategy may be employed. It's called a threat or diematic display. The startled mantis tries to make itself look larger and more threatening than it actually is. Forelegs are held up against the head and prothorax. Mouth may be held agape to show red innards. Black hindwings are unfurled and prominently displayed. Pushed to the limit, such a defensive mantis may then go on the offensive—striking and biting. Individual propensity for diematic display varies like/with temperament.

Captive Environment

Conditions in which the T. sinensis observed for this care sheet were kept:

Temperature: average of 75 degrees F. During the colder months, night time temperatures did occasionally drop to 68 degrees F. However, prolonged drops below 70 degrees F, should be avoided. A space heater remedied the situation.

Humidity: average of 50%.

Misting: twice daily with tap water—in this locality, works just fine.

Communality: as nymphs mature, their appetite for one another also grows. Early separation is recommended. If you must keep together, ample space and a constant supply of food should go a long way in reducing causalities of cannibalism.

Housing: it's easiest to house numerous individuals in spartan plastic cups with paper towel for substrate or no substrate at all. As the nymphs grow, replace the cup with a size larger and so on.

Critter-keepers(8” x 6”) adequately house subadults and adults, but larger enclosures—like aquariums and net cages—are considered more ideal by some. Enhancements for critter-keepers include glue gun affixed popsickle sticks and fake plants/flowers. These additions provide perches and more stable footholds.

The ultimate enclosure may even be none at all. Free range is a very real possibility, and aside from the outdoors, may even be mantis heaven. The authors remaining female T. sinensis (others released) enjoys the run of the bug room/guest bedroom; favorite hangout spots consist of the curtains and the aloe plant. The aloe plant is misted everyday, and roaches are given to her with hemostats.

Feeding response

Feeding response can be viewed as function of temperament. While hunger undoubtedly factors into the equation, even when fed similarly, individual feeding response still appears to fluctuate a great deal. While some are more proactive in the capture of prey, others adopt more of the sit and wait ambush style and prefer smaller prey items. Conversely, there are reports and media of bold and hungry T. sinensis tackling ridiculously large, non-insect prey such as small rodents and hummingbirds.

Type of prey used: D. hydei(fruitflys), A. domestica(crickets), stable flies, blue bottle flies, B. dubia(Guyana spotted roach), N. cinerea(lobster roach), and the occasional katydid, grasshopper, or moth collected outside.

Frequency: everyother day.

Quantity and size: feed til full, e.g., multiple fruit flies per small nymph or mature dubia roach for adult female. Prey items are sometimes leftover between feedings, and while roaches and flies don't seem to pose a threat, crickets should definitely be removed.

Breeding

Sexual dimorphism exists. As mentioned earlier, there is a disparity in adult size. In a side by side comparison of adults, there really is no mistaking one sex for the other. Females are significantly larger—in length and girth. Later instar nymphs and adults may also be sexed by counting abdominal segments(males have eight, females six)or by noting the size of the last segment(much wider in females; segments should be viewed ventrally.

Time needed from female's last molt to copulation: 3 weeks to a month. Presumably, the adult male is ready sooner.

Now for the Fabio romance story:

“Under initial close supervision, breeding took place outside of an enclosure but inside a room with the door closed. The female was occupied with the meal of a cricket. The male was placed just behind her. He immediately took notice and froze, gazing intently at female. As if in slow motion, he gingerly made his advance. Then, there came the point of no return, when he “pounced”, securing himself to the female with his forelegs. The pair was watched until connection was made. At that point, the lights were turned off, and they were left to their own devices. The next morning the female was in the same place. However, the male was found clear across the room.

During the second mating, the male was physically placed onto the female. Also, when things went awry, a bamboo skewer proved useful in separating the quarreling couple.”

Log:

5-22-13: Female molted to adult.

6-14-13: Mated.

?: Mated again.

7-20-13: First ooth laid.

8-30-13: First ooth hatched

*Failed breeding attempts were not recorded, but there were one or two.

Oothecae (Egg Cases)

Described as tan, globular masses, oothecae have sometimes been liken to misshapen ping-pong balls(W. Harrell) or clumps of spray foam insulation(O. McMonigle). At eye level or thereabout, they can be found affixed to the thin branches of overgrown shrubs and small pines. Multiple oothecae are laid, and if conditions are right, they'll usually hatch somewhere between fifty and three hundred nymphs in 4-6 weeks. Although it's considered the norm, nymphs may not come all at once. Some have reported nymphs emerging gradually or an ooth hatching half and half during the course of a week. Diapause is not necessary, but refrigeration can prove useful in delaying the hatch. While in the refrigerator, one must take care to prevent the egg case/s from drying out.

Optional (Health Concerns)

A small number of nymphs suffer from a floppy abdomen. The abdomen literally folds and forms a crease. Presumed to be caused by the perpetual act of hanging upside down, it can prove fatal. Reorienting the enclosure so that the mantis is not always inverted may fix the condition.

ootheca:

(photo: jamurfjr)

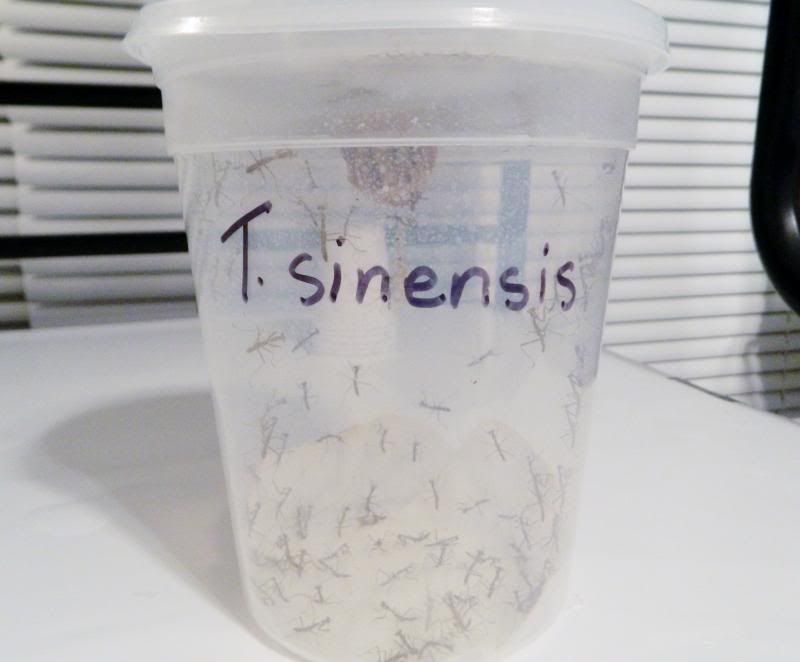

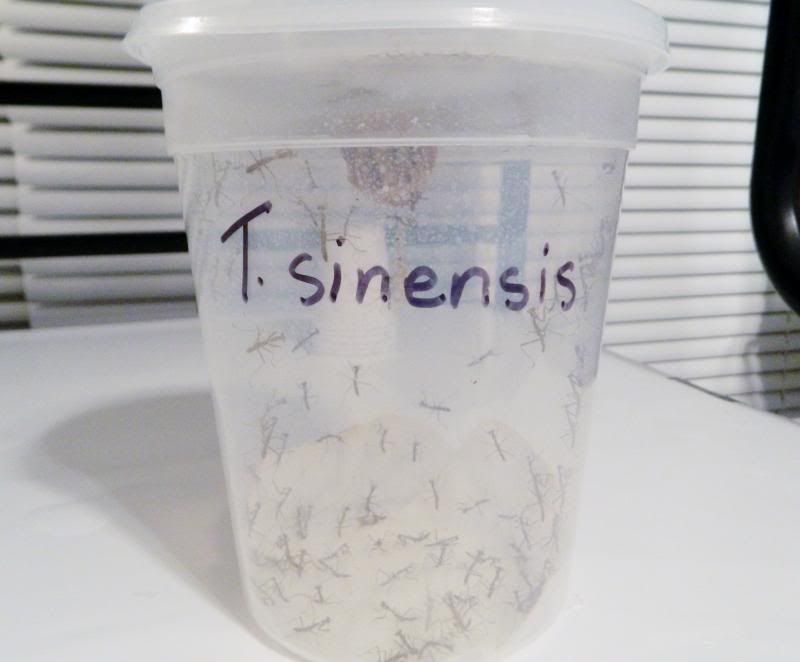

hatch:

(photo: jamurfjr)

L4 nymph:

(photo: jamurfjr)

adult male:

(photo: jamurfjr)

adult female:

(photo: jamurfjr)

Contributors: jamurfjr

Introduction

When asked to envision the stereotypical praying mantis, many Americans conjure up the image of Tenodera sinensis. Along with cousin, T. augustipennis, it's known also as the Chinese mantis. Impressive size coupled with commonness—at least in the eastern half of the US—have influenced this standing. Yet for a child, common doesn't necessarily equate to run of the mill, and such insects are prized for their otherworldly appearance, fascinating behavior, and endearing mannerisms. As the common name implies, the Chinese mantis will always be alien to some extent, for it originated in the far east. Nevertheless, after a hundred years post introduction, it remains touted as an effective means of pest control and now more importantly, an alternative to chemicals(insecticides). Popular amongst gardeners, the oothecae abound just about everywhere—inexpensively sold in local shops and on the internet. All considered, one is subsequently left with little question as to how and why the Chinese mantis has been capturing American affections since the late 1800's.

T. sinensis comes in green, brown, or a combination thereof and blends in very well with its surroundings. Even in brown form, the color green runs the length of the fore-wings' outer edge. A series of vertical stripes/ridges compliment the face. On the ventral thorax, a yellow spot can be discerned between the front legs, and a threat display will reveal a dark set of hind wings. The females measure about four inches. Of considerably less mass, the males are also about a half an inch shorter.

Success in the wild does not guarantee the hobbyist with success in captivity. While later instars and adults may be comparatively easy, raising the smaller nymphs can be downright tough—with many nymphs dying from mismolt or no ostensible reason at all.

Difficulty level: Intermediate.

Development

As with all mantids, insects, etc., temperature and feeding greatly influence development. Under the conditions herein, T. sinensis reaches adulthood in approximately four months, and early instars are achieved in just under two weeks. Later instars take a bit longer. An individual molts roughly seven times. Females may have an extra molt. Lapses in observation and note-taking are responsible for the aforementioned uncertainty. T. sinensis usually lives for eight months to a year. Upon reaching adulthood, females can live another six months. Males, however, live only two to three months as adults.

Behavior/temperament

Individual temperament proves highly variable. Meek exist and so do the audacious. A behavioral spectrum resides between these two extremes.

Cannibalism constitutes a real concern and precludes communal housing beyond early instars.

Camouflage is the first line of defense, but when a Chinese mantis—like many other mantids—is detected and confrontation unavoidable, a different strategy may be employed. It's called a threat or diematic display. The startled mantis tries to make itself look larger and more threatening than it actually is. Forelegs are held up against the head and prothorax. Mouth may be held agape to show red innards. Black hindwings are unfurled and prominently displayed. Pushed to the limit, such a defensive mantis may then go on the offensive—striking and biting. Individual propensity for diematic display varies like/with temperament.

Captive Environment

Conditions in which the T. sinensis observed for this care sheet were kept:

Temperature: average of 75 degrees F. During the colder months, night time temperatures did occasionally drop to 68 degrees F. However, prolonged drops below 70 degrees F, should be avoided. A space heater remedied the situation.

Humidity: average of 50%.

Misting: twice daily with tap water—in this locality, works just fine.

Communality: as nymphs mature, their appetite for one another also grows. Early separation is recommended. If you must keep together, ample space and a constant supply of food should go a long way in reducing causalities of cannibalism.

Housing: it's easiest to house numerous individuals in spartan plastic cups with paper towel for substrate or no substrate at all. As the nymphs grow, replace the cup with a size larger and so on.

Critter-keepers(8” x 6”) adequately house subadults and adults, but larger enclosures—like aquariums and net cages—are considered more ideal by some. Enhancements for critter-keepers include glue gun affixed popsickle sticks and fake plants/flowers. These additions provide perches and more stable footholds.

The ultimate enclosure may even be none at all. Free range is a very real possibility, and aside from the outdoors, may even be mantis heaven. The authors remaining female T. sinensis (others released) enjoys the run of the bug room/guest bedroom; favorite hangout spots consist of the curtains and the aloe plant. The aloe plant is misted everyday, and roaches are given to her with hemostats.

Feeding response

Feeding response can be viewed as function of temperament. While hunger undoubtedly factors into the equation, even when fed similarly, individual feeding response still appears to fluctuate a great deal. While some are more proactive in the capture of prey, others adopt more of the sit and wait ambush style and prefer smaller prey items. Conversely, there are reports and media of bold and hungry T. sinensis tackling ridiculously large, non-insect prey such as small rodents and hummingbirds.

Type of prey used: D. hydei(fruitflys), A. domestica(crickets), stable flies, blue bottle flies, B. dubia(Guyana spotted roach), N. cinerea(lobster roach), and the occasional katydid, grasshopper, or moth collected outside.

Frequency: everyother day.

Quantity and size: feed til full, e.g., multiple fruit flies per small nymph or mature dubia roach for adult female. Prey items are sometimes leftover between feedings, and while roaches and flies don't seem to pose a threat, crickets should definitely be removed.

Breeding

Sexual dimorphism exists. As mentioned earlier, there is a disparity in adult size. In a side by side comparison of adults, there really is no mistaking one sex for the other. Females are significantly larger—in length and girth. Later instar nymphs and adults may also be sexed by counting abdominal segments(males have eight, females six)or by noting the size of the last segment(much wider in females; segments should be viewed ventrally.

Time needed from female's last molt to copulation: 3 weeks to a month. Presumably, the adult male is ready sooner.

Now for the Fabio romance story:

“Under initial close supervision, breeding took place outside of an enclosure but inside a room with the door closed. The female was occupied with the meal of a cricket. The male was placed just behind her. He immediately took notice and froze, gazing intently at female. As if in slow motion, he gingerly made his advance. Then, there came the point of no return, when he “pounced”, securing himself to the female with his forelegs. The pair was watched until connection was made. At that point, the lights were turned off, and they were left to their own devices. The next morning the female was in the same place. However, the male was found clear across the room.

During the second mating, the male was physically placed onto the female. Also, when things went awry, a bamboo skewer proved useful in separating the quarreling couple.”

Log:

5-22-13: Female molted to adult.

6-14-13: Mated.

?: Mated again.

7-20-13: First ooth laid.

8-30-13: First ooth hatched

*Failed breeding attempts were not recorded, but there were one or two.

Oothecae (Egg Cases)

Described as tan, globular masses, oothecae have sometimes been liken to misshapen ping-pong balls(W. Harrell) or clumps of spray foam insulation(O. McMonigle). At eye level or thereabout, they can be found affixed to the thin branches of overgrown shrubs and small pines. Multiple oothecae are laid, and if conditions are right, they'll usually hatch somewhere between fifty and three hundred nymphs in 4-6 weeks. Although it's considered the norm, nymphs may not come all at once. Some have reported nymphs emerging gradually or an ooth hatching half and half during the course of a week. Diapause is not necessary, but refrigeration can prove useful in delaying the hatch. While in the refrigerator, one must take care to prevent the egg case/s from drying out.

Optional (Health Concerns)

A small number of nymphs suffer from a floppy abdomen. The abdomen literally folds and forms a crease. Presumed to be caused by the perpetual act of hanging upside down, it can prove fatal. Reorienting the enclosure so that the mantis is not always inverted may fix the condition.

ootheca:

(photo: jamurfjr)

hatch:

(photo: jamurfjr)

L4 nymph:

(photo: jamurfjr)

adult male:

(photo: jamurfjr)

adult female:

(photo: jamurfjr)

Contributors: jamurfjr

Last edited by a moderator: